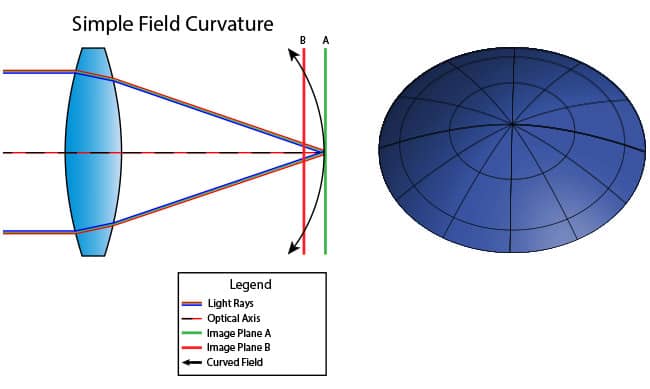

In a simple field curvature scenario like above, the light rays are perfectly focused in the center of the frame, at Image Plane A (where the sensor is). Since the image is curved, sharpness starts to drop as you move away from the center, resulting in less resolution in the mid-frame and much less resolution in the corners. The circular “dome-like” image in three dimensional form is shown to the right of the illustration. If the corner of the image is brought into focus, which would move the image plane closer (Image Plane B), the corners would appear sharp, while mid-frame would stay less sharp and the center would appear the softest. The effect of field curvature can be very pronounced, especially with older lenses.

Like other optical aberrations, field curvature is not limited to photographic lenses – it can be seen in microscopes, telescopes and other optical instruments. While it was possible to bend the image plane with film cameras and compensate for field curvature, it is no longer possible to do that on flat digital image sensors. On top of that, with increased sensor resolution on recent digital cameras, the effect of field curvature is even more relevant and evident today.

Wavy Field Curvature

Unfortunately, field curvature is not limited to the “simple” type illustrated above. Most modern lenses incorporate many different optical elements inside lenses, with some optical elements that are specifically placed to reduce the effect of field curvature. As a result, field curvature can appear in different forms, often with “wavy” curvature, as shown below:

Lenses with wavy field curvature can show sharp center and corner performance, but soft mid-frame performance. If you look at the above illustration, you will see that the shape of the curved image starts out touching Image Plane A in the center, where it is perfectly in focus. Then the image curves in the mid-frame and comes back again in the corners. Hence, if you focus in the center, both the center and the corners would appear sharp, but the mid-frame would appear softer in comparison. If you focused in the mid-frame, which is where the Image Plane B is, the mid-frame would appear sharp, while both the center and the corners would appear softer. This sort of field curvature is a very common occurrence in modern lenses, even professional lenses worth thousands of dollars (see more on this below).

Also, field curvature behavior can vary by distance. Some lenses look good at short range with practically no visible curvature, while exhibiting a rather strong level of field curvature at infinity. The effect of field curvature varies by lens design. Short range lenses (ultra wide, wide and normal) below 50mm typically suffer from curvature problems the most. Telephoto lenses, on the other hand, often have very little or no visible field curvature.

How to find out if a lens has Field Curvature

You might be wondering if the lens(es) you use have field curvature. Before you start your search, you should know that every single lens has field curvature – some stronger than others. While modern optical designs take field curvature into consideration and have specific elements within the optical design to reduce it, most lenses still suffer from it. In fact, even many expensive professional lenses from well-known brands (Nikon, Canon, Zeiss, Leica, etc) have very pronounced field curvature.

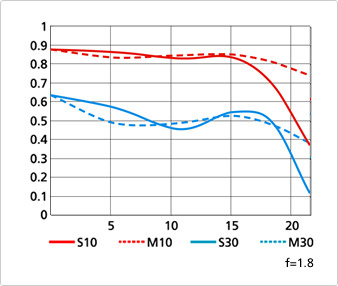

The easiest way to find out if a lens suffers from field curvature is to look at its MTF data provided by the manufacturer. For example, take a look at the following MTF chart from Nikon 28mm f/1.8G:

Note how the lines curve – they start out high, then curve down in the middle, then curve up again, then curve down toward the extreme far. This is a classic example of a “wavy” field curvature, where the center is sharp, the mid-frame is softer, the corners are sharp again and then the extreme corners are soft. I saw exactly the same thing when testing the lens, as evidenced from my Nikon 28mm f/1.8G Review and here are some 100% crops to illustrate the point:

Wide open at f/1.8, the lens suffers from visible field curvature. The center appears sharp, while the mid-frame is much softer in comparison, with corners being better than the mid-frame (if I focused in the mid-frame, both the center and the corner would appear soft). It is a strange thing to see, but this is not the only lens that suffers from such curvature – other Nikon lenses, even the much more expensive Nikon 24-70mm f/2.8G have a similar problem.

How to Reduce Field Curvature

Like other optical aberrations such as Chromatic Aberration, the best way to reduce field curvature is to stop down the lens. If a lens has small to moderate amount of field curvature, stopping down a little will significantly reduce it. But if a lens suffers from heavy field curvature, then you might have to stop down to f/8 or f/11 to reduce it. Sometimes even stopping down to the smallest aperture (at which point diffraction kicks in) does not fully eliminate it.

In the case of the above-mentioned Nikon 28mm f/1.8G, here is what happens at f/8:

As you can see, both center and mid-frame appear much sharper, but the mid-frame is still a little weaker in comparison (which is normal).

Unfortunately, it is impossible to fix field curvature in post-production software such as Photoshop and Lightroom.

Lens Performance Evaluation

It is a well known fact that lenses perform the best in the center of the frame and their image quality can deteriorate toward the edges. In fact, optical performance of lenses is often assessed by the uniformity of sharpness across the frame, so it is a fairly common practice for lens reviewers to demonstrate center and corner performance using various test charts. The problem with most such assessments, however, is that they do not take field curvature into consideration, often arriving at wrong conclusions. When it comes to testing lenses, there are typically two methods.

The first method involves focusing in the center of the frame and then looking at both the center and the corner when evaluating sharpness. The second method is to focus in the center and then focus in the corner separately to assess each separately. Some will acquire focus in the center, mid-frame and corner separately. Both methods can potentially lead to different results and conclusions. The first method would show terrible performance on any part of the image frame that is subject to heavy field curvature, while the second method would show what a lens can potentially resolve in individual parts of the frame, but not the image as a whole.

When testing lenses, our team at Photography Life always uses the first method, which is to acquire focus once in the center and then assess the performance throughout the frame. We believe that this method is the only proper way to assess lens performance because it takes the effect of field curvature into account. If a lens suffers from heavy field curvature, the numbers for corner and potentially mid-frame will be significantly lower. If we were to focus on each section of the frame separately, it would hide the effect of field curvature, which we believe is a serious optical issue to disregard. In addition, when working on the field, one would rarely acquire focus in the extreme part of the frame, separately from the center. Most autofocus systems are designed to be close the the center of the frame.

The only potential problem with our lab assessments is the fact that some lenses show pronounced field curvature at close distances, but have almost none at infinity (important to know for landscape photographers). We are certainly aware of this particular dilemma and we are working on adding additional test results to provide field curvature data for both close focus and infinity. Hence, providing test data only for close distances, or only for subjects at infinity does not provide enough information to fully evaluate the effect of field curvature.

If you are interested in reading more, below is the list of articles on other types of aberrations and issues that we have previously published on The Photographers: